News

2025 Christmas Appeal: Join Us on the Journey

Your generosity makes our mission possible. Would you join us as a monthly donor in 2026?

Introducing Regent’s New Board Member

Regent College is pleased to announce the addition of Andre Van Ryk to its Board of Governors.

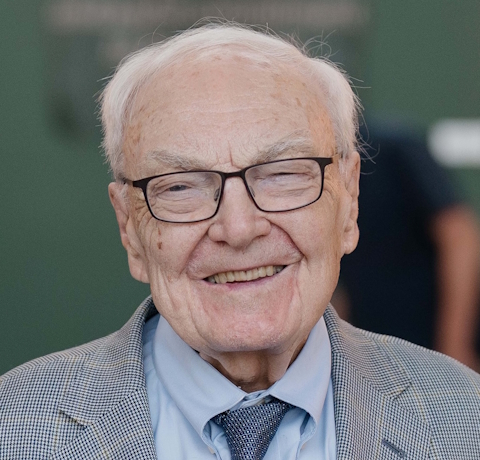

Remembering Luci Shaw

The Regent community remembers the life and legacy of Luci Shaw, a remarkable writer, poet, encourager, and friend.

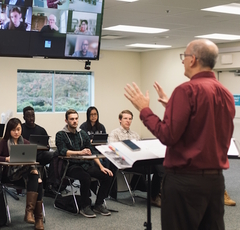

Jonathan Anderson Speaks to Students and Educators About the Theological Imagination

Jonathan Anderson speaks to students and educators about the theological imagination.

George Guthrie Appointed the E. Marshall Sheppard Professor of Biblical Studies

Regent College is delighted to announce that Dr. George Guthrie has been appointed to the E. Marshall Sheppard Chair of Biblical Studies.

Regent College Appoints Rev. Dr. Jerry Hwang as Academic Dean

"We are delighted to welcome Dr. Hwang to Regent College."

Ross Hastings and Julie Lane Gay Receive 2025 Word Guild Awards

Two members of the Regent Community have been honoured for their contributions in the field of Christian Canadian writing.

Introducing the New Regent College Website

Regent College is thrilled to welcome you to our newly redesigned and redeveloped website. Please make yourself at home!

Celebrating the Bruce K. Waltke Chair of Old Testament Studies

The new Bruce K. Waltke Chair of Old Testament Studies was made possible by a generous gift from the Chee family, and will by filled by Matthew Lynch.

Remembering Dick Richards: Sixty Years of Service to Regent College

The Regent College community is sad to note the passing of one of the College’s founders and early leaders.

Jeff Greenman Reflects on His Presidency

At the end of this month, Dr. Jeffrey Greenman will retire from his role as Regent College’s fifth President.

Remembering Bill Atkinson

It is with great sadness that we share the news that a member of Regent’s Board of Governors, our colleague, friend, and brother Bill Atkinson, died.

A Statement on the Violence at Vancouver’s Lapu-Lapu Day Festival

Our hearts are heavy for all those affected by the tragic, heartbreaking violence that occurred at the Lapu-Lapu Day festival in Vancouver on Saturday

The Church and the World Need Regent. And Regent Needs You.

Regent’s 2024–25 fiscal year ends on April 30. Before that date, the College needs to raise $250,000 (CAD) to finish well.

Gardener Julie Lane-Gay Reflects on Coming Changes

In the coming weeks, construction will begin on the former site of Regent’s parking lot.

Student Presentations Highlight Arts and Theology

This spring, Regent is celebrating the artistic gifts and vocations flourishing within our student body.

New Christian Education Fund Will Support Students and Lay Leaders

Regent College is thrilled to announce both a new scholarship for degree-seeking students and a new audit bursary for lay leaders.

Remembering Laurel Gasque

It is with great sadness that Regent College conveys the news that Laurel Gasque, who with her husband Ward was one of Regent's key founders, has died

Caring for Place: Before and After

In the fall of 2022, we launched the Caring for Place project.

Parking Changes at Regent College

Following its 2024 sale to Polygon Homes, the former parking lot site at Regent College has now been fenced off pending construction.

Regent College Board Appoints Paul Spilsbury President

Regent’s Board of Governors is delighted to announce that Dr. Paul Spilsbury has been appointed as the sixth President of Regent College.

Seeking Your Support as We Grow in the Spirit

Every year, Regent reaches out to our global community and invites support through our annual Christmas letter. This year, the Canada Post strike has

.jpg

)

Regent Establishes Advisory Council on Belonging and Equity

Regent College, as a Christian academic community, takes relationships seriously, seeking to live in light of our biblical and theological commitments

Introducing Regent’s Newest Board Members

This October, Regent College’s Board of Governors welcomed two new members: Peter Andersen and Jey Jesuratnam.

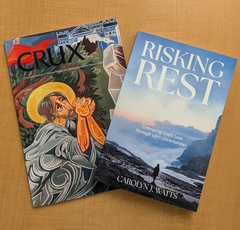

Alumnae Receive Word Awards for Best Non-Fiction Book, Poetry

Regent College is delighted to congratulate two alumnae writers, Carolyn J. Watts and Naomi Pattison-Williams, on their recognition.

Mark Glanville Appointed Director of the Centre for Missional Leadership at St. Andrew's Hall

Mark Glanville, Regent College’s Associate Professor of Pastoral Theology, has been appointed Director of the Centre for Missional Leadership.

Regent College Completes Sale of Its Parking Lot

President Jeff Greenman has announced that Regent College has completed the sale of its parking lot to Polygon Homes.

Regent Audio to Go on Pause

Regent Audio has provided thousands of people with years of service.

Regent College Building Gets a Refresh

Starting in August 2024, Regent College’s building will undergo renovations, primarily on the ground floor.

MACS and THM Programs Updated to Improve Student Experience

As part of its ongoing commitment to providing academic programs that meet the needs of our students, Regent is pleased to announce some recent.

Student Tenants Seek Local Landlords

Regent students need affordable housing in the Vancouver area. The problem isn’t new, but it has continued to grow more acute in recent years.

Regent College Renews Its Moral Vision

Regent College has announced a revised Moral Vision Statement.

Remembering Ken McAllister

It is with great sorrow that we inform you that our friend and colleague Ken McAllister died.

Regent College Launches New Strategic Plan

Following 16 months of collaborative effort by members of Regent College’s staff, faculty, students, and Board of Governors, the Board has unanimously

New Initiative to Help Canadian Church Groups Learn Together

Regent is pleased to announce a new Church Group Learning Initiative that aims to provide flexible financial support to congregations.

.jpg

)

Introducing Scholar-in-Residence Jessamin Birdsall

Dr. Jessamin Birdsall came to Regent as a student in Fall 2022.

-965x918.jpg

)

Regent College Begins Presidential Transition

On February 27, 2024, Jeff Greenman, president of Regent College, announced the beginning of a presidential search and transition process.

MDiv Curriculum Refresh Coming This Fall

Last December, the Regent College Faculty and Senate approved a refreshed curriculum for Regent's Master of Divinity (MDiv) program.

Helping More Students by Expanding Access to Financial Aid

Regent College’s Enrollment and Financial Aid team is delighted to announce that scholarships, bursaries, and other financial aid from Regent College.

Regent Exchange Inspires Small Grants For Church Learning Communities

Over the past five years, the Regent Exchange team accompanied a group of local churches in their exploration of calling.

A Statement on the Recent Violence in Israel and Palestine

At Regent College, we lament the violence, terrorism, and war that has recently engulfed Israel and Palestine.

Introducing Regent's New Board Members

Regent College’s Board of Governors is welcoming five new members this fall.

.jpg

)

2022–2023 Annual Report Highlights Stories of Hope and Transformation

The 2023–2024 academic year got off to a great start last week, as students, faculty, and staff gathered to begin Fall term.

.jpg

)

Meet Regent's Newly-Elected Board Members

In March 2023, Regent College for adding members to the College’s Board of Governors via election by Regent degree-holders.

Parking Lot Rezoning Process Begins

If you visit us on campus, you might notice a large sign on Regent’s lawn.

Remembering Earl Palmer

It is with great sadness that we share the news that Earl Palmer, a beloved former Board member, faculty member, and friend of Regent College, died.

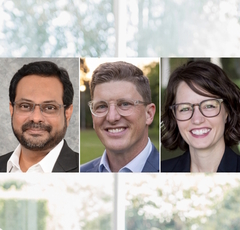

Get To Know Regent's Newest Faculty Members

The Regent community is growing in exciting ways this summer, as our full-time faculty expands to include three new members.

Announcing Regent’s New Assistant Professor in the History of Christianity: Dr. Prabo Mihindukulasuriya

Regent College is delighted to announce the appointment of Dr. Prabo Mihindukulasuriya as Assistant Professor in the History of Christianity.

Announcing the Next Peterson Chair in Theology and the Arts: Dr. Jonathan Anderson

Regent College is delighted to announce the appointment of Dr. Jonathan Anderson as the Eugene and Jan Peterson Associate Professor in Theology.

.jpg

)

Announcing Regent's First Board Member Election

Regent is introducing a new process for adding members to the College’s Board of Governors.

.jpg

)

New Tuition And Registration Info For 2023-24

To ensure the sustainability of our mission to equip students for service in the church, the academy, and the marketplace, Regent’s Board has approved

Bruce Hindmarsh’s New Book Details Storied Life of “Amazing Grace” Writer John Newton

Regent College is proud to celebrate the release of Amazing Grace: The Life of John Newton and the Surprising Story Behind His Song.

Dr. Cindy Aalders Promoted To Associate Professor

The Board of Governors of Regent College is delighted to announce that Dr. Cindy Aalders has been renewed as Director of the John Richard Allison.

Dr. Paul Spilsbury to Serve as Acting President of Regent College

This spring, Academic Dean Paul Spilsbury will assume the role of Acting President of Regent College.

David Ley Appointed To Order Of Canada

Regent College is thrilled to congratulate Board member Dr. David Ley on his recent appointment to the Order of Canada.

Celebration and Gratitude: Announcing the Successful Conclusion of the Deep Roots Wide Reach Campaign

Regent College is delighted to announce the successful conclusion of its Dcapital campaign, which began in 2019 and continued through the end of 2022.