“One of the best gifts for the critical mind and for a living tradition is the gift of a new question.” 1

“Mother God,” were the words my five-year-old son used as he began his prayer, so natural, so effortless. It caught me by surprise, even though we’ve been intentional about expanding his imagination in this way. Though I’ve moved beyond imagining God solely as Father, as male, that image still lives deep in my unconscious, shaped by years of repetition and a world where that was the only reality allowed.

The way I imagined God was profoundly shaped by the idea of God as male. In my mind, that meant power, influence, the voice that gets heard, the one who gets what he wants. Historically, it’s the male figure who rises to the top, fights to stay there, claims the title of provider, head of the house. A theistic God, cast in the image of patriarchy.

But again and again, my expectations of this God, what he would do, how he would act in my life or in the world, failed to match reality. Not just personally, but on a societal scale. Of course, “bad theology” has many roots, but I now see this one, this deeply-embedded gendered image, as especially widespread in mine.

Then, a few years ago, I became a mother. And everything changed.

... And through it all, God was silent.It triggered a flood, a deluge of feelings and questions. Everything I thought I was began to crack, to crumble. I cried out for help, for rest, for relief. And no answer came. I held my son close, loved him with a fierceness that grew by the day, worried constantly, especially in those early days when breastfeeding was hard, when he lost weight and I was drowning in guilt. I was soaked in exhaustion, waking every two to three hours for years. And on the rare nights I got a stretch of sleep, I’d wake up in pain from clogged ducts that turned into mastitis. I would pray, beg, for just one more hour of rest. But nothing changed. I started to panic at any sound, certain it meant he was awake again, and that another night of sleep deprivation was about to begin. And through it all, God was silent.

If God is all-powerful, why not grant me one more hour of sleep? If God is all-loving, why do the women I know seem created to suffer? Couldn’t God do something? Did God even care? Did God understand what it meant to be a woman? Because so much of what I had been taught made it feel like the whole story of womanhood had been written by a cruel, narcissistic being.

Why did my own faltering, imperfect motherhood feel more loving, more present, more sacrificial than the divine parenthood I had been taught to trust? These questions grew, spilling out beyond my own experience. I began to wonder if maybe I was making a fuss over nothing, gaslighting myself into thinking my pain was just part of life. But when I looked around, I saw that all the women around me were suffering too. Not just mothers. I saw war, starving children, broken families, relentless injustice. Again the questions returned: if God is here, active, involved—why is nothing changing?

And perhaps the most painful question of all: why did my own faltering, imperfect motherhood feel more loving, more present, more sacrificial than the divine parenthood I had been taught to trust? I would do anything for my son, give up dreams, wake a hundred times a night, suffer through pain and fear and loneliness. And yet the perfect, all-loving God felt so distant. I was told maybe I wasn’t praying the right prayers, or didn’t have enough faith. But I was depleted. Drenched in depression and hopelessness. Giving everything. And still, it seemed, more was being asked of me.

My faith, as I had known it, died in childbirth.

That death led me back through history. I began to read about women’s stories, of stolen children, of systemic devaluation, of bodies and souls exploited. The more I read, the more I questioned. Had I been expecting God to show up as a man? Was I waiting for a response shaped by male traits, by patriarchy and dominance?

Over time, though I can't name exactly when, my imagination began to shift.

As the book She Who Is reminds us, even our language about God has a history. 2 And my Christian imagination, formed by years of male-centric theology and shaped by my lived experience, began to change. The tension, the inner war between what I was told to believe and what I knew in my body began to settle. 3

Now, I find peace in something new.

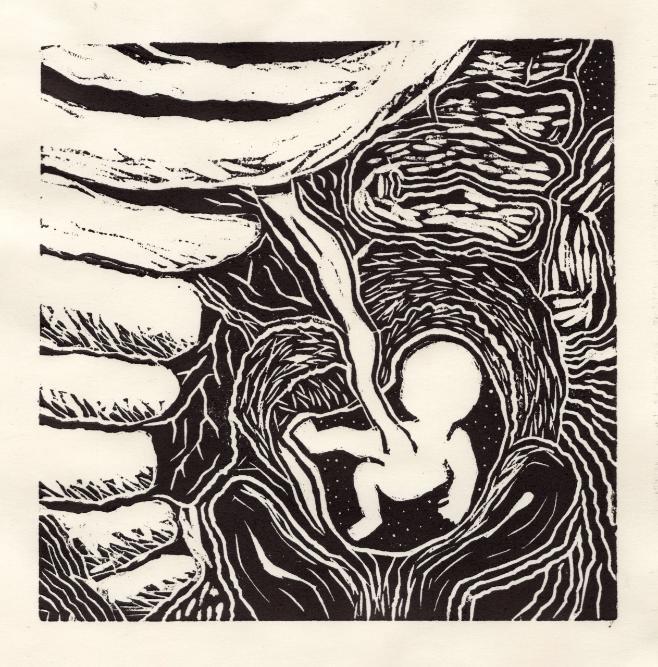

My God is a Mother. The Mother.

Maybe what I once saw as silence wasn't absence, but presence misunderstood.Today, I believe in and envision a Mother God whose body has been broken for me, whose blood has been poured out. A God who, though endlessly loving and fierce in her care, a God who would tear off her own arm to feed her children, has no political power, no economic clout, no value in the eyes of the world. A Mother God who would die holding her child while bombs fall from the sky.

Maybe what I once saw as silence wasn't absence, but presence misunderstood. Not inaction, but the underground, quiet, steady, devoted movement of divine femininity. Not the thunder of victory, but the whisper of a lullaby. Not the conquering force, but the suffering companion. Not a God who stomps through walls, but one who kneels beside me in the dark. A God whose strength is not dominance, but endurance. Whose love does not always fix, but holds. Sustains. Suffers with. Dies with me, over and over again.

Recommended Reading:

- Aldredge-Clanton, Jann. 1990. In Whose Image? God and Gender. Crossroad, 1990.

- Claassens, L. Juliana M. Mourner, Mother, Midwife: Reimagining God’s Delivering Presence in the Old Testament. Westminster John Knox Press, 2012.

- Cleveland, Christena. God Is a Black Woman. HarperOne, 2022.

- Marga, Amy E. In the Image of Her : Recovering Motherhood in the Christian Tradition. Baylor University Press, 2022.

- Peeler, Amy L. B. Women and the Gender of God. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2022.

- Rae, Eleanor, and Bernice Marie-Daly. Created in Her Image: Models of the Feminine Divine. Crossroad, 1990.

- Van Wijk-Bos, Johanna W. H. Reimagining God: The Case for Scriptural Diversity. Westminster John Knox Press, 1995.